By Perry Firth, Graduate Student, Seattle University Community Counseling, and Project Assistant, Seattle University’s Project on Family Homelessness

Suppose someone asked you to picture a veteran.

What do you see?

If you are like most people, you visualize a man. Maybe this man is strong and fit- looking. Or maybe he has an old ‘Nam hat, and still wears a faded combat jacket.

You might even visualize somebody who is homeless and asking for money, their sign proclaiming that they are a veteran, and that they’ve fallen on hard times. Anything helps.

While many veterans are men, and some of these men struggle with homelessness, the unfortunate reality of this stereotype is that it ignores a growing segment of the homeless population: women veterans.

As women’s presence in the military has grown – they now make up nearly 15 percent of active-duty personnel – they have faced a unique set of challenges both while serving and post-discharge.

That’s where Seattle Stand Down is stepping up this year. The Stand Down is a one-of-a-kind event where homeless veterans—both male and female—can get the help they need.

MST: A major factor in female vet homelessness

Among the challenges to women in the military is rampant sexual assault and harassment, followed by an increased risk for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression and homelessness as they re-enter civilian life.

The high rate of sexual assault in the military, called military sexual trauma (MST), is rooted in the military’s ingrained patriarchy, its ambivalence about the role of its female service members, and its low enforcement of military law.

The structure of the military contributes to the problem as well.

If a woman is sexually assaulted, she is technically supposed to report the offense up her chain of command, who should then take action. Unfortunately, there is no guarantee that her commander will do anything, or, for that matter, that he wasn’t the one who attacked her.

Ultimately, the likelihood that her attacker will be prosecuted is low, while the likelihood that she will be blamed and her story either minimized or denied is high.

These factors, wedded with a military system that emphasizes tough-guy masculinity, has led to an environment uniquely set up to both enable and forgive sexual assault.

The end result?

In today’s U.S. military, one in three women is sexually assaulted – overwhelmingly most often not by enemy forces, but by their fellow soldiers.

Even more distressing for the women who experience this: Unlike a civilian sexual assault, the highly structured and close-knit nature of a military unit ensures that a victim will be forced to see their rapist again and again, potentially every day.

She may even have to take orders from him.

All of these systemic stressors compound the initial trauma of the rape itself, leading to a high likelihood that the effects will continue past a woman’s discharge, complicating her ability to reintegrate to civilian life and access services.

To learn more about all of this, I had the pleasure of talking to Rebecca Murch, Seattle University Community Counseling graduate student, and executive director of the upcoming third annual Stand Down event. Like all the organizers of the Stand Down, Rebecca is a veteran herself; she served in the U.S. Navy from 1988 to 1990.

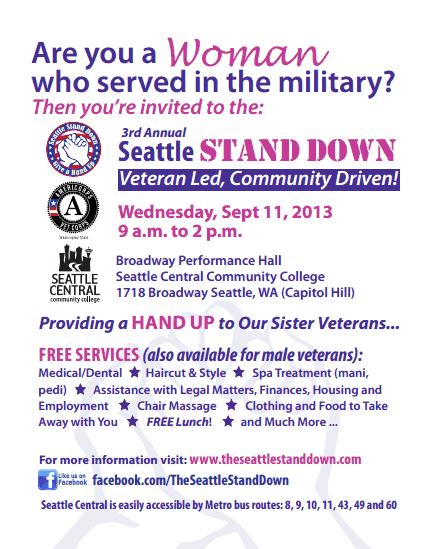

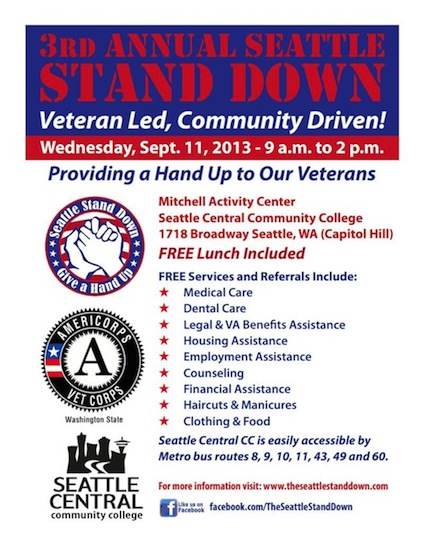

The Stand Down, Sept. 11

The Stand Down is a volunteer effort geared toward homeless veterans. It’s driven by student veterans at Seattle University, Seattle Central Community College and other universities and colleges, and various partner organizations. Now in its third year, the event brings together a spectrum of social service agencies into one location, making it easier for the veterans to access a variety of needed services such as shelter and housing resources, gear like sleeping bags and tents, a meal, basic medical care and legal counseling.

Building on prior years’ success, the organizers hope to attract more veterans than ever, and more specifically, they hope to attract more women.

This year’s emphasis on specialized outreach toward women is rooted in the reality that in past years the Stand Down has attracted primarily male veterans who are homeless. Last year they attracted only 38 women. While in comparison to the 300 men who attended, this number is low, it is a great improvement over the grand total of two women who had attended in the first year.

According to Rebecca, the low attendance of women vets at the Stand Down reflects their lower utilization of services in general, especially those run by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). In turn, she says, their lower use of services is a call to action for military and service providers to design outreach and care that takes into account the unique barriers and experiences of female veterans. And building on last year’s woman-focused efforts, Rebecca is making sure that this year the Stand Down does just that.

“Am I even a veteran?” and other barriers

Barriers faced by women veterans range from inadequate civilian job and life skills training, to a dearth of childcare, to many women’s mistaken belief that because they didn’t actually serve in a combat role, they are not technically veterans and therefore not entitled to VA benefits. The VA’s confusing bureaucracy and long wait times doesn’t make women veterans’ job any easier either, Rebecca said.

However, one of the biggest barriers to accessing services, and one that is linked to homelessness for women veterans, is military sexual trauma. According to the Service Women’s Action Network, of homeless female vets, 40 percent have experienced sexual assault. Moreover, military sexual trauma is the biggest predictor of PTSD for women who have served in the military, in comparison to their male peers whose PTSD is typically combat-related.

What this means is that women veterans, those homeless and housed alike, often do not feel safe and supported as they try to navigate the VA healthcare system.

If they visit a VA hospital, they will find that there is little female-centric medical care and facilities. They will discover a strong institutional bias toward PTSD treatment that is combat-related, effectively ignoring the cause of the average female veteran’s PTSD. Physically, they will be in the minority. Everywhere they look, there will be men. For a woman who has been raped, seeing men everywhere while trying to use a system that has not been set up to accommodate her can be so traumatic that she quits seeking care.

Moreover, if they try to utilize housing and shelter services for veterans, they can be forced to share a confined space with men a space that can lack locking doors, and requires sharing a bathroom.

Cumulatively this means that many women veterans disassociate from their veteran status, give up hope of accessing housing and support services from the VA, and fall between the cracks.

Rebecca, however, is determined to reach these women, and to that end she has used her knowledge of the effects of military sexual trauma and the needs of women veterans to bring them into the Stand Down.

Reaching Women Veterans

The Stand Down outreach efforts include using different language and fliers to attract women veterans.

It has involved targeting women veterans by asking if they have ever served in the military, not whether they are veterans. This language is geared toward women who might not realize that they are veterans, and therefore eligible for veteran services.

It has also involved canvassing areas that are frequented by women who are homeless, because so many of them are reluctant to stay in shelters, preferring to sleep in cars or couch-surf.

Under Rebecca’s guidance, the Stand Down facilities have also been tailored toward women. The women vets who attend will be in their own building, the Broadway Performance Hall, away from the men. This is one of the most important elements in creating an environment that feels safe for women attendees, Rebecca said. As needed as these services are, there will be women too intimidated to access them in a room full of men.

Rebecca told me that the Stand Down organizers have also implemented a “buddy system” for the women. Female volunteers will escort any women who want to access the services provided in the men’s section, but feel too intimidated to go alone. Created because there are not enough providers to exactly duplicate the services provided to both the men and women, the buddy system tries to bridge that gap.

Hearing about the lengths that Rebecca and her team are going to in supporting women veterans is inspiring, but also heartbreaking. I am glad they are doing it; I just wish it weren’t necessary in the first place.

Our society can do better. So can our military.

To that end, some changes that would help women re-integrate to civilian life include a VA system that is more sensitive to female physical and psychological needs; better job training; better recruitment of women to VA services; more women-only VA shelters and housing; better mental health counseling; and an abandonment of the victim-blaming attitude that continues to re-traumatize so many women.

It didn’t take long during my interview with Rebecca to see the great passion she has for helping veterans. She told me that she didn’t want this article to be about her; after all, this is about women veterans and the Stand Down.

I couldn’t agree more.

That being said, I can’t help but be impressed by Rebecca’s willingness to use her own military experiences and connections to help women veterans. It is people like her who are making this world a better place.

What you can do

As always, advocacy and education is an important step in righting society’s wrongs.

- If you know a woman veteran who’s unstably housed, tell her about the Stand Down.

- Let your legislator know that you would like better funding for women-focused shelters, especially those that serve women vets. Emphasize the importance of trauma-informed care and mental health counseling.

- If you would like to become involved in the Stand Down, visit their website for a list of volunteer opportunities. An effort like this takes a large corps of volunteers.

- If you want to learn more, I would highly recommend the award-winning documentary The Invisible War by director Kirby Dick. It chronicles the experiences of military women who were sexually assaulted and their fight to receive care and bring their attackers to justice.

- Another way to learn more is to visit our project’s site to see a TV interview with Seattle-area veteran advocate Sheila Sebron and Col. Mary Forbes (Ret.) of the Washington State Department of Veterans Affairs (WDVA), and read a report about the challenges faced by women veterans.

The Stand Down is Wednesday, Sept. 11, 2013, 9 a.m.-2 p.m. at Seattle Central Community College. For more information contact Rebecca Murch at [email protected] or visit Seattle Stand Down’s website.

Our “From Soldier to Civilian” blog series is examining barriers that veterans, and women veterans in particular, face as they re-enter civilian society. Are you a veteran who would like to share your story? Please contact Firesteel Advocacy Coordinator Denise Miller at [email protected].