Part Seven in our series on homelessness and poverty in the public education system

Written by Perry Firth, project coordinator, Seattle University’s Project on Family Homelessness and school psychology graduate student

We’ve outlined how homelessness and poverty impede academic success. Now, it’s time to describe some innovative ways schools are helping their students who are homeless, or who have intense mental health needs.

Therefore, in this, the last part of our series on homelessness and poverty in the public education system, I have the great pleasure of profiling two schools and one educational philosophy, all of them cutting edge.

- The first one we’ll talk about is the joint housing-school partnership between McCarver Elementary in Tacoma and the Tacoma Housing Authority, called The McCarver Elementary School Special Housing Program.

- Then we’ll profile First Place Scholars, Washington’s first charter school, and one that is specifically focused on helping impoverished students and their families.

- Finally, we’ll discuss how schools throughout the country are adopting a “trauma-informed” educational philosophy to better meet the needs of their youth living with toxic stress.

The McCarver Elementary School Special Housing Program

Located in a low-income area in Tacoma, Wash., McCarver Elementary has the highest population of students experiencing homelessness in the area. Subsequently, in recent years it has also had a very high student turnover rate as these students move around with their families. According to the Tacoma Housing Authority, the turnover rate had been as high as 179 percent. That means that the entire student body had changed over more than once by the end of the school year.

And this high mobility had been creating not only low levels of academic success for the school’s homeless students, but for the school as a whole.

Therefore, in 2011, the school entered into an innovative housing-school program with the Tacoma Housing Authority (THA) in an effort to improve academic outcomes for the entire school. It’s called the McCarver Elementary School Special Housing Program.

Since the program’s initiation in 2011, the school and THA have been providing affordable subsidized housing and case management to 50 of the school’s families who are homeless, including 79 kids. To be eligible for the program, the parents must have a student who is in kindergarten, first or second grade.

More than just providing housing, however, it asks parents to commit to various academic and life goals, including increasing financial self-sufficiency. For example, THA starts out paying most of the rent for the families; however, by year five they are expected to have taken it over themselves.

On the academic front, families are asked to carve out time and space for their students to study, and to keep their students in the program.

Funded by multiple community partners, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the program is rooted in the idea that children will learn better if they are not switching schools, and if their families are stably housed.

So far, the results are impressive.

Some impressive preliminary results

The most recent report from Geo Education & Research, the third-party program evaluator commissioned by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, clearly shows how stabilizing a child’s family can lead to academic growth.

Completed in January of 2014, the report shows some exciting findings:

- The program has “made considerable progress toward their goals of improved performance in school for children, housing stability and eventual financial self-sufficiency.”

- Student mobility rates have decreased, not only for children in the program, but for the whole student body.

- Students in the program have made “substantial strides” in reading in both years one and two (the years we have data on). Notably, the reading scores for the students who are homeless in this program are much higher than the reading scores of students elsewhere in the district, who are not in the program. These high reading scores are positively correlated with attendance. That is, one of the reasons these children are making such leaps in reading is because their lives are stable enough for them to consistently be in school.

- In year one, the reading scores of the students in the program showed a 22 percent gain/improvement. Students in the program are also getting in less trouble at school (e.g., they are behaving better).

- The parents in the program have also grown “as students.” Twenty have earned a GED, diploma or professional certificate since entering the program.

Finally, the success of the students in this program is positively changing the overall culture of the school. According to the teachers in the school, more parents are engaged in their children’s education overall, and there has been an improvement in parenting skills.

These are some impressive and heartening results.

Here are just a few of the reasons why the report authors think the program is having such success:

- It is meeting a key need of the student body population — affordable, stable housing and wrap-around services.

- Accessibility: THA has two caseworkers in the school where families and school staff can meet with them. For me, at least, this jumps out as so important; families who are struggling need help and service delivery to be easily accessible.

Something I would add about student success parallels a theme discussed throughout this blog series. Just as problems for parents can become problems for children, success for parents becomes success for children. That many of the parents in the program are growing their skills can only help their children achieve in school.

First Place Scholars

First Place Scholars, formerly a private elementary school located in Seattle, Wash., just became the state’s first charter school. With a 25-year history of serving students living in poverty, it has always focused on empowering students at risk of school failure.

Seattle University Journalism Fellow Lee Hochberg visited the graduation ceremony at First Place School in 2010 for his report on how well schools comply with the McKinney-Vento Homeless Education Assistance Act. The report below aired on the PBS Newshour in October 2010.

While First Place’s funding source may have changed (now it will be publicly and philanthropically funded), its commitment to children living in poverty remains. The school continues to be specifically focused on supporting the academic achievement of impoverished students who have also experienced trauma, including those who are homeless.

Here are some key student demographics:

- 98 percent of the students are eligible for free and reduced lunch.

- 20 percent have been identified as needing special education.

- 20 percent don’t speak English at home.

With only 98 students, the school is able to provide targeted services, including:

- Very small classes, only 14-16 children per class, with multiple student aides. Further, the teachers have experience teaching traumatized children.

- Extended day programs including science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics.

- Extensive monitoring and documentation of student outcomes and program success.

- An integrated and coordinated education and mental health services delivery model called Coordination Care Team that addresses problem behavior and emotional health.

- Connecting parents to social services — all families get case management.

- Mental health services, onsite tutoring and mentoring, and health screenings.

- School supplies, clothes, shoes, hygiene items (you can see how essential this is to students experiencing homelessness).

While the charter school is still young, this is another example of a school doing everything it can to help students living in poverty. Just that a school like this exists gives me hope. While charter schools certainly generate a lot of controversy, it is undoubtedly positive that the school is able to provide such a high level of support to its learners.

Its educational philosophy is also in line with the research I have outlined throughout this series, namely that children living in poverty need stabilizing supports to be successful in school.

This philosophy is evident in the diverse supports First Place provides its students, and also in its housing management program. Yes, the school manages and case manages 41 permanent housing units. Students may be part of this housing program, or they may live in other transitional housing in a partner agency. Or, a family may reside in the unit and choose to send their child to another school.

Having just read about the McCarver School/housing program in Tacoma, I am starting to notice a trend: For students to be successful in school, they need housing!

Now we move on to our final profiled program, trauma-informed schools.

Trauma-informed schools

At least since last year, I have been aware of a growing trend in education: taking neuroscience research on how trauma and toxic stress impacts the developing brain and impairs learning, and using it to shape educational practices. One of the most exciting developments is trauma-informed schools, and Washington state is a national leader.

Whenever brain research is used to guide educational practice, I get excited; it means that research is making its way out of the ivory tower and doing real good in the lives of students.

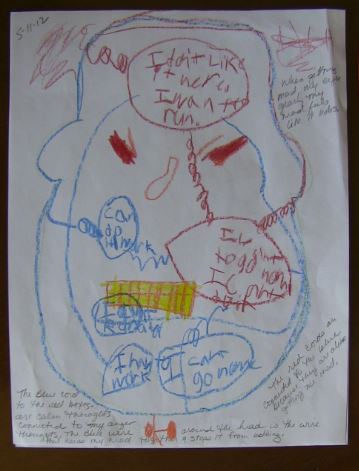

Much of this research (and subsequent educational policy) is rooted in the understanding that students simply cannot learn when they are experiencing high levels of stress or trauma. Further, many of the behaviors that give teachers such a hard time, like explosive, disruptive behavior, or apathy and disengagement, are the effects of trauma showing up in the classroom.

The reality is that in every classroom, there will be many students who have experienced enough adverse child experiences (ACEs) that they cannot process and regulate their emotions in healthy or adaptive ways. Therefore, they end up getting in trouble in school, failing to grow their academic skill set, and eventually dropping out.

This means that if schools want to reach these students, they have to change their educational practices. Instead of suspending the angry young man because of a classroom outburst, his behavior needs to be interpreted in light of any trauma he has experienced. You can see that this is a new twist on interpreting student behavior.

So in schools that have adapted this philosophy of trauma-informed teaching, teachers are given a foundation in what trauma can do to their students, how it may impact their academic achievement and behavior, and what this means for how they respond to child behavior. While this approach is not meant to let students off the hook for poor behavior, it is designed to foster compassion on the part of teachers and administrators, allowing them to calmly and empathetically respond to challenging behavior.

It asks teachers to praise the good things they see a student doing, as opposed to pointing out when they are making a mistake. Ultimately, trauma-informed schools are all about fostering an environment where students feel safe, secure, and cared for.

It also means teaching the students themselves way to calm down, handle their emotions, and express their needs appropriately.

To present a more cohesive definition of what it means to be a trauma-informed school, I’ll share the essential components according to the Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative (TLPI), an excellent resource for those interested in learning more about this.

Trauma-informed schools:

- Understand that trauma is common, and that it negatively impacts learning and emotional health. This is an understanding shared by every single adult at the school, including support staff like bus drivers.

- Believe that children cannot learn unless they feel safe, and that children act out when they feel unsafe. Therefore, the first step in creating an environment where students can learn is creating an environment where they feel safe.

- Have a holistic understanding of how children succeed. They recognize and address the relationships between key life domains. They understand the importance of “relationships with teachers and peers; the ability to self-regulate behaviors, emotions, and attention; success in academic and non-academic areas; and physical and emotional health and well-being.” (From TLPI)

- Understand that trauma and adversity can cause children to disconnect from those around them. Trauma-informed schools make explicit attempts to connect their students to the school community. They also provide them opportunities to practice burgeoning skills.

- Recognize that a classroom full of many traumatized students is too much for one teacher to handle. Therefore, they move away from the typical educational model where one teacher is responsible for all of the students in her class. Rather, responsibility for students is shared throughout the school team.

- Finally, they understand the challenges and needs of their surrounding community. This enables them to plan for some the challenges and needs their students are bringing to school.

Trauma-informed schools in Washington state

According to the organization ACEs Too High, Washington (along with Massachusetts) is actually leading the way for the new trauma-informed approach.

This may be because 13 out of every 30 students in a Washington classroom has experienced at least three adverse childhood experiences, whose effects include toxic stress.

In the Spokane School District, there are now six elementary schools that have adopted a trauma-informed approach. And Lincoln High School, in Walla Walla, has also adopted the practice. According to an interview published on the ACEs Too High website with the school’s principal, there have been encouraging results. For example, school suspension and expulsions have dropped since he implemented a trauma-informed system in 2010.

2009-2010 (Before new approach)

- 798 suspensions (days students were out of school)

- 50 expulsions

- 600 written referrals

2010-2011 (After new approach)

- 135 suspensions (days students were out of school)

- 30 expulsions

- 320 written referrals

Looking at this data, I think about what it means for the cycle of poverty that many of these children with high ACE scores are trapped in. After all, school discipline data doesn’t just measure infractions; it measures school connectedness. So if a school is able to implement a system where students don’t get suspended and expelled at high rates, which keeps them connected to school, we are one step closer to ensuring that students already crippled by poverty and chronic stress aren’t harmed further.

Conclusion: “What keeps me going”

Writing this series has been quite the experience. It isn’t easy to spend time researching and writing about the many barriers faced by children who are homeless and in poverty, especially when the framework used to explain child outcomes is toxic stress. After all, children are resilient; yet toxic stress, homelessness, and trauma can have lasting consequences.

That is why it felt so appropriate to end with a discussion of some cutting edge-practices in public education. These practices may not be widespread, but for the children reached, they are making a difference. From schools that are connected to housing, to schools harnessing research on how toxic stress harms children, these pockets of innovation are inspiring.

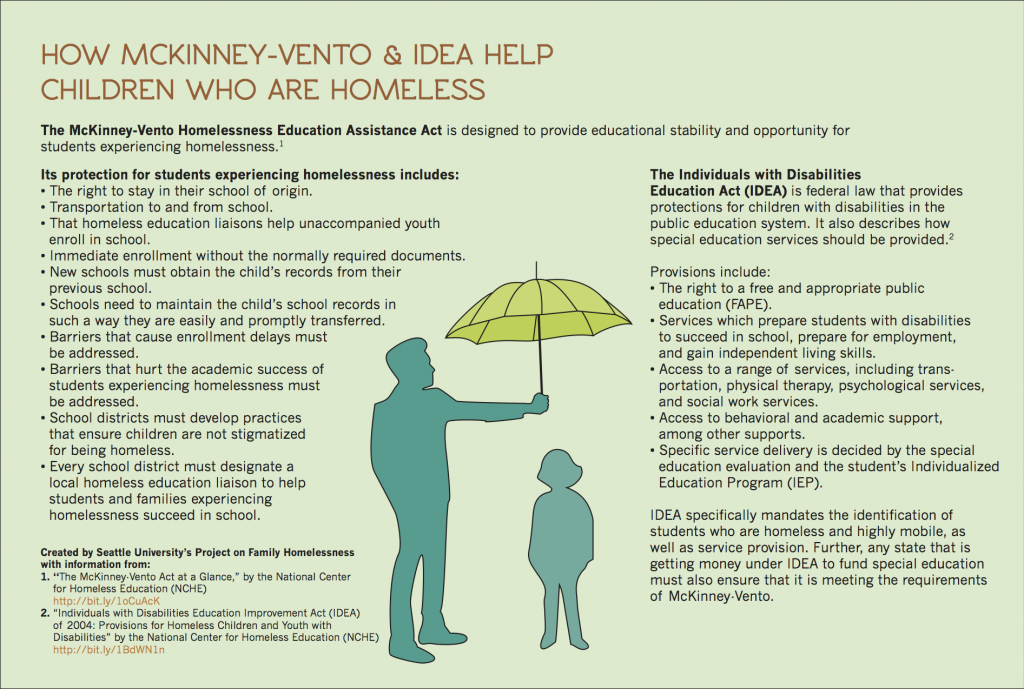

As a refresher, this infographic highlights how federal policy helps children who are homeless and in need of special ed services. But it takes more than policy.

So, here is the bottom line: Children who are homeless and in poverty, and who are suffering the consequences of toxic stress, are in trouble. They do need a community and school system that cares, and a nation that prioritizes their needs. They do need safe, affordable housing, access to special education if necessary, and wrap-around services for families.

However, as we’ve seen in this final post, there are people out there working tirelessly on their behalf. And where this is happening, there have been improvements. There have been successes.

And so I’ll conclude with this: “Through it all, school is probably the only thing that has kept me going. I know that every day that I walk in those doors, I can stop thinking about my problems for the next six hours and concentrate on what is most important to me. Without the support of my school system, I would not be as well off as I am today. School keeps me motivated to move on, and encourages me to find a better life for myself.” —Formerly homeless student and LeTendre Scholar, quoted by National Center for Homeless Education.

What you can do

- Visit the Trauma-informed Learning website and download their free document Helping Traumatized Children Learn.

- Read Paul Tough’s How Children Succeed and Whatever it Takes. Both of these books do a great job of talking about toxic stress, how children learn, and what they need to be successful in school. Also, they are true page-turners.

- Learn more about the innovative schools in your community; ask what they need and how you can help.

- Let’s keep the discussion going! Please submit a comment below with your ideas, or e-mail the author at firthperry@gmail.com.

Read other posts in this series

- Part One | Hungry, Scared, Tired and Sick: How Homelessness Hurts Children

- Part Two | Homelessness, Poverty and the Brain: Mapping the Effects of Toxic Stress on Children

- Part Three | Homelessness and Academic Achievement: The Impact of Childhood Stress on School Performance

- Part Four | More Barriers to Learning: Homelessness and the Special Education System

- Part Five | A Web of Risk: Homelessness and the Special Education Category “Emotional Disturbance”

- Part Six | McKinney-Vento, IDEA and You: Strategies for Helping Homeless Children With Disabilities